A love letter to Empirical Design in Reinforcement Learning by Andrew Patterson, Samuel Neumann, Martha White, Adam White JMLR 25 (2024) 1-63 (from this Bluesky post

These aren’t the heroes we deserve, but they are the heroes we need.

I mean, look at this opening paragraph. This is written to be read and understood, not to impress and overwhelm. Not for the handful of reinforcement learning researchers in the world, but for the slightly larger handful of people trying to make it work on their machine.

The paper is refreshingly concrete, fully loaded with examples, case studies, recommendations, and pitfalls. It's a map to the landmines in reinforcement learning. It's what I would have gifted my younger self.

It's easy to lie to your readers in any ML work, but in reinforcement learning it's also easy to lie to yourself. The authors shine a bright light on all these sneaky backchannels. Designer's curse. Untuned baselines. Hypothesis After Results Known (HARK). Cherrypicking of all sorts.

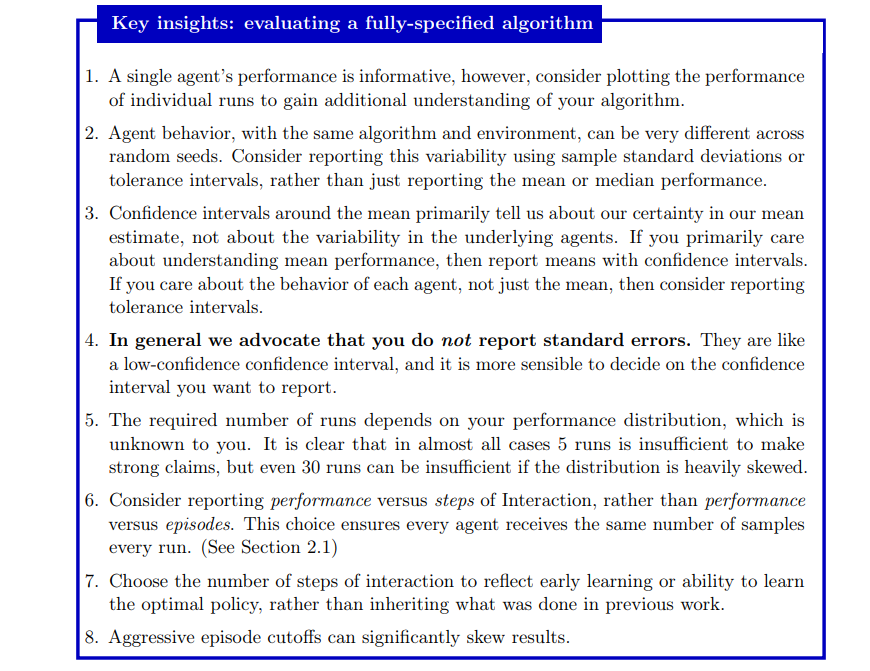

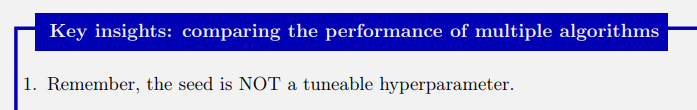

And for the love of the great Flying Spaghetti Monster DO NOT TUNE ON YOUR SEED. Just don't.

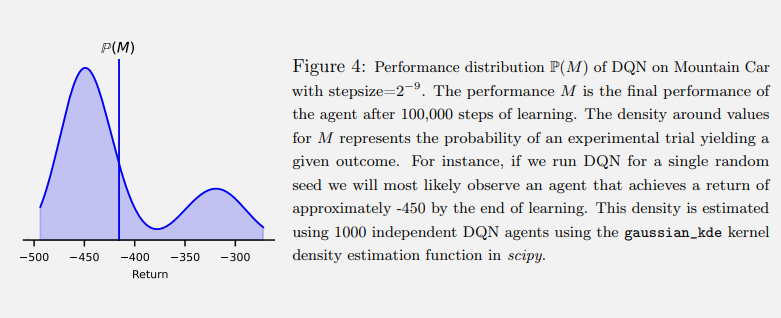

As an unexpected treat the authors have genuinely grown-up conversations with us about statistics. Reinforcement learning runs are so computationally intense and then add in hyperparameter sweeps, it's easy to see how representing distributions and confidence intervals falls by the wayside. No more.

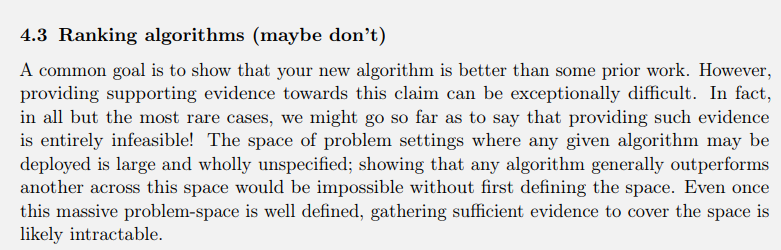

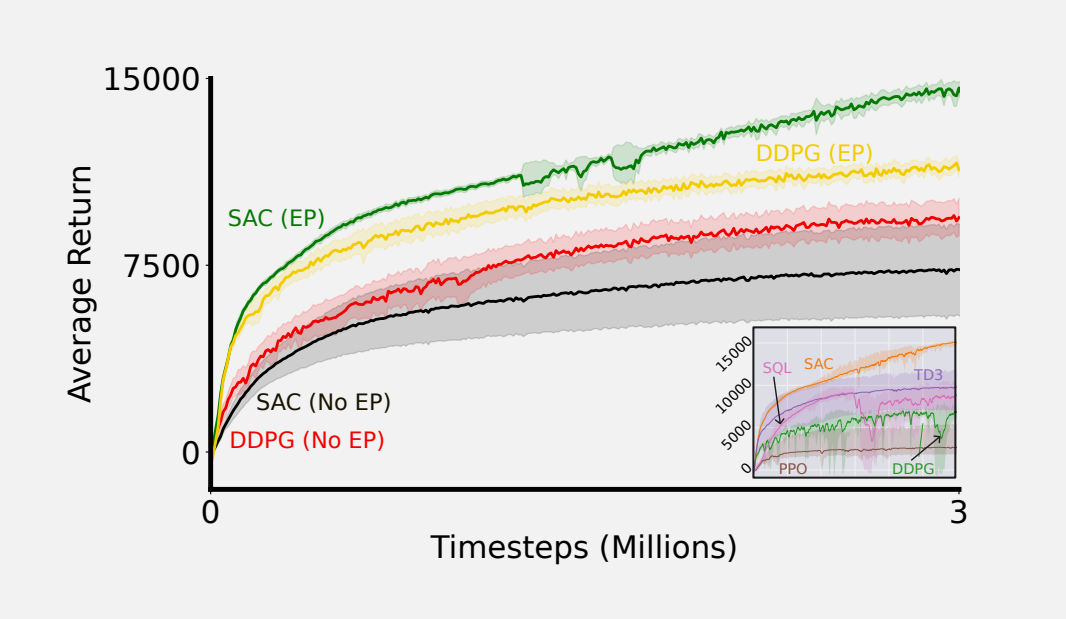

But the ride doesn't stop there. The authors take an ax to the root of the tree of ML leaderboard-based publishing. They make a strong case that reinforcement learning comparisons are all but infeasible to do in a meaningful way.

This low key refutes the entire ML conference industrial complex.

The authors even take it a step further. If you can always choose environments in which your algorithm excels, then the interesting question becomes which conditions and why. Each RL algorithm is a special and unique snowflake. What if the real science is the quirks we discovered along the way?

As an absolute tour de force, the authors attempt what has so far only been dreamed of - reproducing results from another paper. They prove that it's not a path for the faint of heart, but they get there, and in style.

You like lists? The authors finish with a list of common errors in reinforcement learning experiments.

You like lists? The authors finish with a list of common errors in reinforcement learning experiments.

- Averaging over 3 or 5 runs

- Reusing code from another source (including hyperparameters) as is

- Untuned agents in ablations

- Not controlling seeds

- Discarding or replacing runs

- Cutting off episodes early

- Treating episode cutoffs as termination

- Randomizing start states

- HARK’ing (hypothesis after results known)

- Environment overfitting

- Overly complex algorithms

- Choosing gamma incorrectly

- Reporting offline performance while making conclusions about online performance

- Invalid errorbars or shaded regions

- Using random problems

- Not reporting implementation details

- Not comparing against stupid baselines

- Running inefficient code

- Attempting to run an experiment beyond your computational budget

- Gatekeeping with benchmark problems

and they note that this list will be appended to in an accompanying online blog post.

The only thing the paper lacked IMO was it should have ended with mic drop.